The Role of Disgust Imagery in Social Movements

by Dr. Krista Hiddema and Lauri Torgerson-White, M.S.

Introduction

Social movements have long resulted in both systems-level and individual changes that create a world more aligned with the ethical perspective of the current population. These movements often begin with grassroots organizing by individuals who see a need for change and are spurred forward more quickly when a variety of actors engage in diverse individual actions which collectively create change at a societal level. The farm animal advocacy movement is one such movement with a diverse range of actors who engage in various tactics, including but not limited to protests, education, legal advocacy, corporate engagement, government lobbying, animal rescue, and the use of often difficult-to-view photographic and videographic imagery (hereafter referred to as disgust imagery) procured through undercover investigations in the industrial animal agriculture industry.

This research paper seeks to answer three questions about the role of disgust imagery in farm animal advocacy in Canada:

What do Canadians know about intensive animal agriculture?

How do Canadians learn about intensive animal agricultural practices?

What do Canadians do when they become aware of how meat, dairy, and eggs are produced?

This paper will then explore animal activism in Canada within the context of social justice theories and will treat the matter of disgust imagery as an essential part of that activism.

Question One: What do Canadians know about Industrial Animal Agriculture?

To answer this first question, we must begin by defining intensive animal agriculture (also referred to as modern animal agriculture) We will then discuss what Canadians know about intensive animal agriculture while exploring the desire of Canadians, largely driven by their concern for animal ethics, to learn more about how their food is produced.

Intensive animal agriculture is comprised of the industries that breed, raise, transport, and slaughter farm animals, particularly cows, pigs, chickens, turkeys, and fishes to produce meat, eggs, and dairy for human consumption. The breeding and raising facilities of intensive animal agriculture are formally defined as any farming system that involves crowding large groups of animals into confined indoor spaces such as stalls, cages, or sheds (Intensive/Factory Farming, 2019). These facilities breed, raise, and slaughter animals largely out of public view. Routine practices found in intensive animal agriculture differ significantly from those seen historically as part of animal husbandry, whereby small farms were known to provide a high level of individual care for their animals, including letting them roam free and engage in a variety of preferred natural behaviours (Anomaly, 2019). Notably, intensive animal agriculture is responsible for upwards of 90% of all animal protein production worldwide (Anthis & Anthis, 2019).

The average Canadian has little knowledge of the routine practices used to produce meat, eggs, and dairy. In 2019, the Canadian Centre for Food Integrity found that 91% of Canadians knew little to nothing about modern farming practices, while only 9% indicated that they knew a lot. In addition, 60% of survey respondents indicated they were interested in learning more about modern farming practices (Connecting with Canadians, 2019). Research shows that this desire to learn more about animal agriculture is driven largely by ethical questions related to intensive animal farming practices (Faucitano et al., 2017).

The ethical concerns elicited by intensive animal agriculture include, but are not limited to, animal welfare (the subjective experience of the animals) and the impacts that industrial animal agriculture has on human health as has been evidenced through the proliferation of zoonotic diseases including Covid-19 (Environment, 2020). Each of these two concerns will now be addressed.

Battery hens. Photo: We Animals.

Animal Welfare: While Canadians seem to have a limited understanding of the impacts that intensive animal agriculture can have on animal welfare, research shows that Canadians support natural living conditions for animals as well as for animals to live in environments that are conducive to positive emotional states (Spooner et al., 2014). Canadians in that same study objected unanimously to the confinement of animals during their lives (e.g., cages for hens that lay eggs), which is a standard practice in intensive animal agriculture.

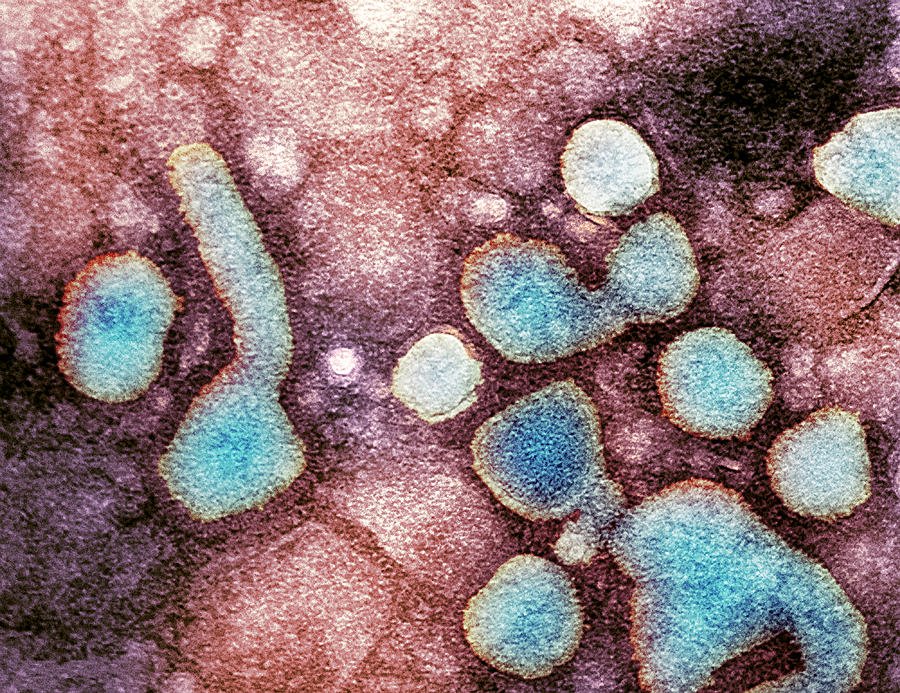

Human Health: As in the case of animal welfare, while Canadians may not fully realize the link between intensive animal agriculture and zoonotic diseases, the information is readily available (Environment, 2020). The 2021-2022 avian influenza outbreak has been covered extensively in Canadian media, including articles in the CBC, the Globe and Mail, and the National Post, among others, making clear that outbreaks were connected to intensive animal agriculture operations (Casey & The Canadian Press, 2022; Silberman, 2022; The Canadian Press, 2022). And of course, Canada’s beef industry was hard hit by the 2003 case of bovine spongiform encephalopathy, or mad cow disease (Petigara et al., 2011).

Cargill plant in London, Ontario. Photo: CTV News

One of the most prolific zoonotic diseases seen in decades is Covid-19. While all Canadians are at risk of contracting Covid-19, the animal agriculture industry, specifically meatpacking, has experienced some of the largest outbreaks (Taylor et al., 2020). This was evidenced at the High River Cargill meatpacking plant in High River, Alberta, and at the Cargill facility in London, Ontario (Business Wire, 2020; McCarthy, 2021).

The outbreak was so egregious in Alberta that the Alberta Health Services created a dedicated Task Force to respond to COVID-19 outbreaks associated with meat packing facilities, both at the workplaces themselves, and in the communities surrounding these facilities (Alberta Health Services, n.d.).

In addition, a recent study found that people working directly in the intensive animal agriculture industry are some of the most at risk for other zoonotic diseases including campylobacteriosis, cryptosporidiosis, E. coli, listeriosis, salmonellosis, Lyme disease, Q fever, and avian and swine influenza, among others (Adam-Poupart et al., 2021; Business Wire, 2020). Canadian poultry farms have recently been hard hit by most recent avian influenza outbreaks that are sweeping the globe, a disease with the potential to cause the next global pandemic (Government of Canada & Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 2011; Sutton, 2018; Yamaji et al., 2020).

H5n1 Avian Influenza Virus Particles, Tem is a photograph by Nibsc which was uploaded on May 11th, 2013.

Indeed, a July 2020 report co-authored by the United Nations Environment Programme and the International Livestock Research Institute listed seven anthropogenic factors driving zoonotic disease emergence like the recent avian influenza outbreaks. Three are directly related to growth of intensive animal agriculture: 1) increased demand for animal protein, 2) the rise of intensive and unsustainable farming, and 3) changes in food supply chains (Environment, 2020). In order to stem the mounting threat to the environment and to human health, many scientists have called for the worldwide discontinuance of intensive animal agriculture (DeGrazia, 1999; Livestock Systems, n.d., “ZOONOSES,” 1951; Wiebers & Feigin, 2020).

Understanding this interconnection between animal health and human health has been long recognized not only by the United Nations, but also by the World Health Organization through the One Health Initiative (Home, 2020). The One Health Initiative links veterinary health and human health recognizing that human health, animal health, and ecosystem health are inextricably linked, and provides an unprecedented opportunity for the average citizen to make an impact on the health of the planet by making more informed food choices.

Question Two: How do Canadians learn about Industrial Animal Agricultural?

When looking to better understand the animal welfare implications of practices that take place within industrial animal agriculture facilities, 45% of Canadians say they trust animal advocacy groups to inform them, and 29% of Canadians go so far as to indicate that they hold these advocacy groups responsible for providing credible information about industrial animal agriculture (Connecting with Canadians, 2019).

The most common way in which Canadians become aware of these practices is through photographic and videographic evidence taken by animal advocacy groups. And, when Canadians are exposed to these photographic and videographic materials, they often find the images difficult to review as they can cause a plethora of negative emotions (McQuaig, 2020).

One such emotion, disgust, is an emotion that is comprised of three components. First, the person performs a cognitive appraisal, thus personally interpreting and evaluating the eliciting situation. Second, the person experiences a unique physiological response of nausea combined with a disgust face. Third, the person exhibits behavioral avoidance of the eliciting stimuli (Rozin et al., 1999; Shook et al., 2019). In other words, when a person sees undercover footage of farm animals being treated cruelly, they think cognitively about the meaning of the situation, feel nauseous while making a face that indicates disgust, and then stop watching the footage. Disgust imagery is often lumped together with shock and fear-inducing imagery under the shockvertising label (Bennett, 2008; Klara, 2012; Lupton, 2012). Regardless of whether the imagery evokes feelings of disgust, fear, or shock, in all cases, research has demonstrated that such tactics are at least sometimes effective in provoking consumers to adopt a call to action (Dillard & Shen, 2018; Koch et al., 2022; Morales et al., 2012).

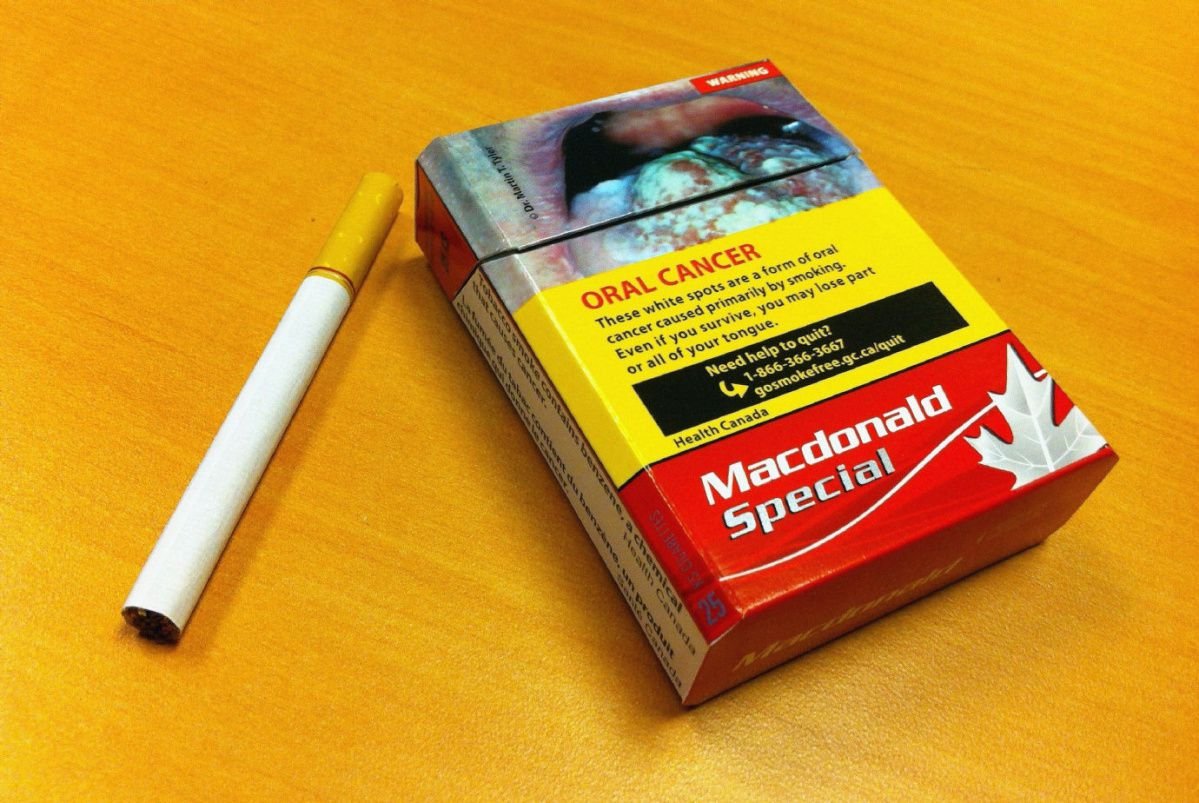

Anti-smoking campaigns, anti-drug campaigns, fundraising for child protection organizations, pro-life campaigns, and animal rights campaigns have all utilized disgust imagery in their social campaigns to increase the persuasiveness of their calls to action (Allred & Amos, 2017; Brown & Smith, 2007; Deckha, 2008; Leshner et al., 2011). More recently, disgust imagery has been suggested to increase compliance with COVID-19 public health measures (Mermin-Bunnell & Ahn, 2022).

Disgust imagery on tobacco packaging in Canada. Photo credit: Denis Savard / THE CANADIAN PRESS

Disgust in anti-smoking campaigns

To better understand the use and effectiveness of disgust imagery, we will examine, as a case study, its use in the anti-smoking movement and then discuss how disgust images are similarly used in animal advocacy campaigns.

In 1965, almost half of Canadians smoked, compared to just 13% today (Ljunggren & Shakil, 2022; Historical Trends in Smoking Prevalence, 2017). This sharp decline was the result of activism that began after Judy LaMarsh, the then Minister of National Health & Welfare stated, in 1963, "There is scientific evidence that cigarette smoking is a contributory cause of lung cancer and that it may also be associated with chronic bronchitis and coronary heart disease" (“Canada’s War on Smoking Turns 50,” 2013). Thirty years later, in 1993, the World Health Organization adopted a worldwide public health treaty that required nations to implement a range of public health measures related to tobacco consumption including large and clear health warnings that could be “in the form of a picture” (Gajalakshmi et al., 2000; Hammond et al., 2004; Reducing Tobacco Use: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2000). This was despite the tobacco industry’s argument that disgust imagery, also referred to as graphic warnings, would cause excessive emotional distress, people would avoid them, and that the graphic nature would undermine the credibility of the tobacco industry’s message, and thus decrease tobacco consumption (Ad Hoc Committee of the Canadian Tobacco Industry, 1969; Hammond et al., 2004; Key Area Paper--Public Affairs: Smoking and Health - Health Warning Clauses. Bates No. 502605183, 1992). The anti-smoking movement resulted in the introduction of graphic warning labels on Canadian cigarette packages in December 2000.

The World Health Organization has undertaken significant research on ways to reduce smoking rates and has found graphic imagery to be effective in reducing tobacco consumption and in preventing nonsmokers from becoming smokers. In addition, in a survey of 616 adult Canadian smokers, one in five people reported smoking less because of the labels. Participants reported negative emotional responses like those predicted by the tobacco industry including fear (44%) and disgust (58%), and the study found that those who experienced these negative emotions were more likely to have quit, attempted to quit, or reduced their smoking (Hammond et al., 2004). An experimental study in 2017 corroborated these findings when the authors found that anti-tobacco advertisements containing disgust imagery evoked the highest intentions to quit smoking as compared to advertisements that did not contain disgust images (Clayton et al., 2017).

While the literature cited above was based largely on self-reported data, a study that utilized epidemiological data from the Canadian National Population Health Survey came to the same conclusions. Graphic warnings significantly decreased the odds of a person becoming a smoker and increased the odds of a person attempting to quit smoking (Azagba & Sharaf, 2013). These results indicate that disgust imagery is effective at reducing tobacco use by Canadians.

Tobacco use remains the leading preventable cause of illness and premature death in Canada, killing approximately 48,000 people each year (Ljunggren & Shakil, 2022). Given the success of disgust imagery in reducing tobacco consumption, Canada has now become the first country in the world to propose the addition of warning labels on each individual cigarette, citing the need to “reach people, including the youth, who often access cigarettes one at a time in social situations.”

Disgust imagery in animal advocacy

Similarly, disgust imagery has been used for decades by animal advocacy organizations to raise public awareness regarding industrial animal agricultural practices by highlighting the fact that animal cruelty is commonplace in the industry. More recently, disgust imagery has been proposed as a tactic (in addition to warning labels) to reduce meat consumption for health reasons (Kaufmann, 2022; Koch et al., 2022).

Because the use of disgust imagery in health-based anti-meat campaigns is only in the exploratory stage, we will instead focus our discussion on the use of disgust images in campaigns designed to reduce or eliminate individual consumption of animal products.

Undercover investigations into intensive animal agriculture operations entered the Canadian landscape when the animal advocacy organization, Mercy For Animals Canada (MFA), expanded its operations from the United States to Canada. The first undercover investigation in Canada by MFA was released to the public in 2012 and was based on photographic and videographic evidence of the inner workings of one of Canada’s largest pork producers, Puratone in Arborg, Manitoba (“Animal Abuse Alleged at Manitoba Hog Farm,” 2012). Hidden-camera footage exposed thousands of pregnant pigs confined to filthy metal gestation crates so small the animals were unable to even turn around or lie down comfortably, workers were seen firing metal bolts into pigs’ skulls, pigs with open wounds and pressure sores from rubbing against the bars of their tiny cages, and workers slamming piglets into the ground and leaving them to suffer and slowly die. Since then, Canadian mainstream media sources from award-winning investigative news show W5, to prime-time news programs such as CTV and CBC, to major media outlets such as The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Star, and the National Post, to local radio stations and community newspapers have been showing Canadians often difficult to see evidence of the realities of intensive animal agriculture. The goal of these undercover operations is to obtain photographic and videographic images that will be shared with the public to elicit disgust, attitudinal change, and eventually behavioral change.

The impacts of disgust imagery in the animal protection movement have been studied by scientists worldwide to varying conclusions. In a 1998 study, the persuasive effect of these disgust images in eliciting attitudinal change about animal experimentation was explored (Nabi, 1998). The authors, who relied upon the knowledge that disgust often incites behavioral avoidance, found that disgust imagery (i.e., graphic images of monkeys with head injuries) reduced support for animal experimentation, even when the messaging of the campaign was in favor of animal experimentation. In 2009, Scudder and Mills investigated the impacts of a campaign by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) that utilized undercover footage of a pig farm and found that the imagery was effective at both eroding trust in meat companies as well as increasing PETA’s perceived credibility (Scudder & Mills, 2009). A 2013 study that investigated the impact of media coverage of cruelty to cattle in slaughterhouses elicited disgust, sadness, and pity for the cattle, but did not result in action to stop this cruelty (Tiplady et al., 2013). While studies have yielded mixed results, a meta-analysis by Fernández in 2020 found that regardless of the outcome, disgust imagery is an important component of the animal advocacy movement in ensuring that the public learns about the realities of industrial animal agricultural practices (Fernández, 2020).

Question Three: What do Canadians do when they become aware of how meat, dairy, and eggs are produced?

We will now address the actions Canadians take when photographic and/or videographic evidence of how meat, dairy, and eggs are produced is released to the public.

To provide the most accurate answer to this question, we will rely on explicating the responses by Canadians based on the release of videographic evidence of dairy production at the largest dairy facility in Canada at that time, Chilliwack Cattle Sales (CSS) in Chilliwack British Columbia on June 9, 2014. While it can be difficult to measure the impacts of viewing this footage on the Canadian public, it is possible to hypothesize a link between the resulting policy changes and the Canadian public’s stated commitment to improved animal welfare (Spooner et al., 2014).

To do so, we will review the responses to the dairy industry disgust imagery obtained by MFA from CSS from The British Columbia Milk Marketing Board, Saputo, the British Columbia Provincial Government, and the public.

The British Columbia Milk Marketing Board (BCMMB)

The BCMMB is made up of Canadians who are appointed to serve terms of three years and are expected to have knowledge of the dairy industry and supply management. Board members work collaboratively to “promote, control and regulate the production, transportation, packing, storing and marketing of milk, fluid milk and manufactured milk products within British Columbia” (About, 2019).

When the CCS dairy production video was released to the public in June 2014 (Chilliwack Cattle Sales, 2014, the Canadians on the BCMMB responded by filing Amending Order 16 (Amending Order 16, 2015). Amending Order 16 was conditionally approved on September 3, 2014 and became effective on October 1, 2014. This order ensured that the National Farm Animal Care Council (NFACC) Dairy Code of Practice became mandatory for all BC dairy farmers and as such, held all farmers to a baseline level of animal welfare practices.

The BCMMB has the power to determine who can produce and sell milk in the province, and in cooperation with other provincial marketing boards, in the entire country. By law, all milk producers in BC must sell milk through the BCMMB, and hence, their power if substantive.

Saputo

Saputo, the largest dairy company in Canada, on June 1, 2015, announced its commitment to improving animal welfare across its entire global supply chain as a direct result of the release of the CCS disgust imagery (Atkins, 2015; Saputo, 2015).

The Saputo policy was comprehensive and included zero tolerance for any act of animal cruelty, it supported training for the handling of cattle, the elimination of tail docking, the use of pain control when dehorning or disbudding, a commitment to suspend receiving milk from any farm where it believes abuse to be taking place, and further commitment to only reinstate receiving milk once an independent audit and a corrective action plan have been implemented.

BC Provincial Government

Also in direct response to the release of the CCS disgust imagery (Dairy Code Strengthens Expectations of Care for B.C. Cows, 2015), the province of British Columbia incorporated the NFACC Dairy Code of Practice into the BC Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act (BCPCA) in 2015 by introducing regulation 24.02 (BC Reg 34/2019 | Animal Care Codes of Practice Regulation, n.d.; Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, n.d.). Prior to this regulation, section 24 of the BCPCA provided that a person could not be convicted of cruelty to animals if they were using reasonable and generally accepted practices of animal husbandry regardless of any distress they have caused to an animal. The definition of reasonable and generally accepted was nebulous and left to interpretation. The addition of regulation 24.02 as a result of the release of the Chilliwack Cattle Sales video footage replaced the reasonable and generally accepted practices to be those practices set by NFACC.

In addition, in 2019, the BC Provincial Government incorporated additional NFACC codes of practice into the BCPCA (see Section 4 of the BCPCA, (BC Reg 34/2019 | Animal Care Codes of Practice Regulation, n.d.)). These now include the codes of practice for beef cattle, bison, dairy cattle, domestic equine species, domestic swine, foxes, mink, poultry, rabbits, sheep, and veal cattle.

The BC Provincial Government also filed charges against Chilliwack Cattle Sales (CCS) and several employees (British Columbia v. Chilliwack Cattle Sales, 2016). Representing the people was Crown Council James (Jim) MacAuley. The Crown’s submissions included i) a DVD, ii) submission of facts, and iii) a book of authorities. During the hearing on December 18, 2018, Crown had a large-screen television in the room turned in such a way that both the judge and the gallery could see it clearly (K. Hiddema was in attendance). Crown proceeded to play the DVD showing no less than twenty video clips and providing an explanation prior to playing each one of what was being shown. Particularly noteworthy clips included:

workers kicking a downed cow repeatedly in the face,

a worker standing on a metal rail, repeatedly beating a cow with a cane and saying, “This is much more fun than milking”, and

workers attaching milking machines to the testicles of bulls.

Justice Robert Gunnel served twenty charges as documented in the Information dated February 29, 2016, sworn by Justice of the Peace J. Lunde (British Columbia v. Chilliwack Cattle Sales, 2016). Notably, CCS President Kenneth Kooyman pleaded guilty to three charges of animal cruelty on behalf of the farm itself, and his brother Wesley Kooyman, a CCS director, pleaded guilty to one charge personally.

General Public

Research has shown that Canadians know very little about what happens behind the closed doors of intensive animal agriculture facilities, but that they want to know (Connecting with Canadians, 2019). Perhaps more importantly, the desire for this information is driven by a commitment to animal welfare (Spooner et al., 2014). While the CCS case study presented above does not provide direct insight into the responses of each Canadian when they learn how their meat, dairy, and eggs are produced, it does provide clear evidence that the use of disgust imagery can create policy changes that align the practices of intensive animal agriculture with the ethical views of Canadians.

Social Activism Requires a Multitude of Intentional Actions

Social activism theory tells us that social campaigns, whether intended to elicit societal change to reduce rates of tobacco consumption or to reduce consumption of meat, dairy, and eggs, must include a multitude of intentional actions taken by individuals and organizations. These can range from protesting to government lobbying, and, in totality, they work to bring about changes in society (Dumitrascu, 2015).

In examining social activism theory, particularly noteworthy are political scientist Gene Sharp’s work studying the politics of nonviolent action, and theorist and social movement organizer Bill Moyer’s Movement Action Plan (MAP) Model for Social Organizing (Moyer et al., 2001; Sharp, n.d.). Each of these will be examined in the context of the work of animal activists to secure photographic and videographic evidence of intensive animal agriculture.

The Politics of Nonviolent Action

Sharp’s work was birthed from his 1968 doctoral dissertation and led to his groundbreaking voluminous 1973 book “The Politics of Nonviolent Action,” which was divided into three parts: Part One – Power and Struggle; Part Two – The Methods of Nonviolent Action, Political Jiu-Jitsu at Work; and Part Three – The Methods of Nonviolent Protest and Persuasion (Sharp, n.d., 1968). Sharp specifically discussed the need for civil disobedience in social activism campaigns, stating that part of civil disobedience must include the countering of “illegitimate laws as a method of political noncooperation [that] may be practiced by individuals, groups or masses of people, and by organized bodies” (Sharp, n.d., 1968, p. 340).

Sharp went on to note that civil disobedience is often undertaken reluctantly by individuals who may not want to engage in civil disobedience, but who are compelled to do so based on their deeply held beliefs as a means to disrupt what they view as an unjust or oppressive system – referred to by Sharp as revolutionary civil disobedience.

Civil disobedience was also discussed by Mohandas Gandhi. Sharp particularly noted that Gandhi referred to civil disobedience in democratic environments as a necessary tool to combat local wrongs and that in order to raise people’s awareness of a particular wrong, it requires self-sacrifice by activists.

To aid activists in preparing for these acts, in Part Three of his book, Sharp included a catalog of 198 individual actions that could be taken by activists such as wearing symbols, displaying flags, vigils, picketing, publication of names, labour strikes, and sit-ins, and provided definitions and examples of each of the actions.

In all cases, the intention was to raise public awareness.

Movement Action Plan Model for Social Organizing

A second theory, Moyer’s MAP Model for Social Organizing, provided a social activism model based on four roles that activists can assume, and included an eight-stage map that all social movements go through over a period of years or decades (Moyer et al., 2001).

Moyer and colleagues described the four activist roles: a) the citizen, referring to the involvement of ordinary citizens in activism; b) the rebel, those who are most visible in a movement, usually the front face of media and in the public spotlight; c) change agents, those who are focused on educating the public; and d) the reformer, those who are engaged in lobbying and parliamentary work.

The Eight Stages of Social Movements can occur in a variety of orders, and movements may even experience occasions of moving backward through the stages, but in all cases, the goal of powerholders (corporations and/or government) is to prevent the movement from moving forward. The eight stages include (1) normal times, (2) proving the failure of institutions, (3) ripening conditions, (4) social movement take-off, (5) identifying crisis of powerlessness, (6) majority public support, (7) success, and (8) continuing the struggle.

The MAP Model, in a democratic environment, where the social problem under consideration is not well known by the general public, highlighted the need for the rebel role to assume the important job of educating ordinary citizens. For animal activists, since most Canadians know very little about intensive animal agriculture, this role is particularly important, and the primary way in which education takes place is by showing Canadians how meat, dairy, and eggs are produced.

Rebels are in part defined as individuals who “literally use their bodies” in a variety of ways and are distinguished as the “first to be recognized publicly as challenging the status quo” - the rebel’s work is “sometimes dramatic, exciting, courageous, risky, and, occasionally, even dangerous” (Moyer et al., 2001, p. 24). Rebels are also often at the center of the movement and at the center of public attention in stage four: take-off.

The take-off stage is characterized by a shock that is usually elicited through television or other similar media sources and goes from being unknown to becoming a social problem that is being discussed. Moyer and colleagues reference that this usually occurs as a result of a trigger event that brings the issue to the general public, citing examples such as the arrest of Rosa Parks and the Seattle demonstrations of December 1999.

Both Sharp’s and Moyer’s work highlight the need for social movements to be propelled forward by a variety of actors engaging in a multitude of actions. These actions must reflect the reality of the social wrong they are seeking to right, which, in the case of the use and abuse of animals for food, that is the video graphic imagery of the realities of industrial animal agriculture.

Conclusion

History has shown that social change happens when brave and passionate people work together in a myriad of ways to counter oppressive systems. This bravery and passion have fueled the civil rights movement, the feminist movement, the LGBTQ+ rights movement, the green movement, and countless other movements worldwide, none of which would have happened without people like Rosa Parks, David Suzuki, Malala Yousafzai, Malcolm X, Nelson Mandela, all of whom were seen as rebels for their views.

A fair and just society needs rebels. They are an important and critical part of social progress. Rebels should be celebrated not vilified. Have we not learned this lesson yet?

Positionality

Dr. Krista Hiddema, B.A., M.A., CHRP, SHRP, is an ecofeminist academic and activist. She has led a dozen undercover investigations into factory farms and slaughterhouses in Canada, has lobbied the federal government for improved animal transportation regulations, and consults with animal protection organizations on matters of strategic planning, board governance, and organizational development. She is regularly called upon by Canadian media for matters of farmed animal welfare and has been featured in four episodes of W5, Canada’s most-watched documentary program.

Lauri Torgerson-White, M.S., is the Senior Director of Research and Animal Welfare at Farm Sanctuary where she uses her expertise as an animal welfare scientist to design and implement research to understand more about the inner lives of farmed animals while also working with the care teams to ensure positive welfare for all residents. She has authored peer-reviewed publications on animal welfare, personality, and cognition; taught university-level biology and nutrition courses; and traveled all over the world visiting farms to better understand the needs of farmed animals.

References

About. (2019, November 26). BC Milk Marketing Board. https://bcmilk.com/about/

Adam-Poupart, A., Drapeau, L.-M., Bekal, S., Germain, G., Irace-Cima, A., Sassine, M.-P., Simon, A., Soto, J., Thivierge, K., & Tissot, F. (2021). Foodborne and Animal Contact Disease Outbreaks: Occupations at risk of contracting zoonoses of public health significance in Québec. Canada Communicable Disease Report = Releve Des Maladies Transmissibles Au Canada, 47(1), 47.

Ad Hoc Committee of the Canadian Tobacco Industry. (1969). A Canadian tobacco industry presentation on smoking and health: a presentation to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health, Welfare and Social Affairs. Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence, 1579–1689.

Alberta Health Services. (n.d.). COVID-19 Meat Processing Plant COVID-19 Outbreaks. Retrieved July 18, 2022, from https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/topics/Page17115.aspx

Allred, A. T., & Amos, C. (2017). Disgust images and nonprofit children’s causes. Journal of Social Marketing. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JSOCM-01-2017-0003/full/html

Amending Order 16. (2015, March 9). BC Milk Marketing Board. https://bcmilk.com/download/amending-order-16/

Animal abuse alleged at Manitoba hog farm. (2012, December 11). CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/animal-abuse-alleged-at-manitoba-hog-farm-1.1258963

Anomaly, J. (2019). Intensive Animal Agriculture and Human Health. In B. Fischer (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Animal Ethics (1st ed) (pp. 167–176). Routledge.

Anthis, K., & Anthis, J. R. (2019). Global farmed & factory farmed animals estimates. https://sentienceinstitute.org/global-animal-farming-estimates

Atkins, E. (2015, June 1). Dairy giant Saputo responds to animal abuse video. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/dairy-giant-saputo-releases-animal-welfare-policy/article24731245/

Azagba, S., & Sharaf, M. F. (2013). The effect of graphic cigarette warning labels on smoking behavior: evidence from the Canadian experience. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 15(3), 708–717.

BC Reg 34/2019 | Animal Care Codes of Practice Regulation. Retrieved June 23, 2022, from https://www.canlii.org/en/bc/laws/regu/bc-reg-34-2019/latest/bc-reg-34-2019.html?searchUrlHash=AAAAAQAFTkZBQ0MAAAAAAQ&offset=0

Bennett, J. (2008, March 3). This Is Your Brain On Scary Ads. Newsweek. 151, 13.

British Columbia v. Chilliwack Cattle Sales, LTD. 2016 BCPC 63894. Information, Court Identifier 3521:PRA, Agency File Number SPCA:14-17342.

Brown, S. L., & Smith, E. Z. (2007). The inhibitory effect of a distressing anti-smoking message on risk perceptions in smokers. Psychology & Health, 22(3), 255–268.

Business Wire. (2020, April 24). Cargill Death and Disease a 21st-Century Version of the Westray Explosion. Financial Post. https://financialpost.com/pmn/press-releases-pmn/business-wire-news-releases-pmn/cargill-death-and-disease-a-21st-century-version-of-the-westray-explosion

Ljunggren, D. & Shakil, I. (2022, June 10). Canada, in a world first, proposes health warnings on individual cigarettes. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/canada-world-first-proposes-health-warnings-individual-cigarettes-2022-06-10/

Canada’s war on smoking turns 50. (2013, June 17). CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/canada-s-war-on-smoking-turns-50-1.1303483

Casey, L., & The Canadian Press. (2022, March 31). Canadian farmers warned to be “extremely vigilant” amid growing outbreaks of bird flu. National Post. https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/canadian-farmers-warned-to-be-extremely-vigilant-amid-growing-outbreaks-of-bird-flu

Chilliwack Cattle Sales to fire 8 workers caught on tape abusing cows. (2014, June 11). CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/chilliwack-cattle-sales-to-fire-8-workers-caught-on-tape-abusing-cows-1.2670098

Clayton, R. B., Leshner, G., Bolls, P. D., & Thorson, E. (2017). Discard the Smoking Cues-Keep the Disgust: An Investigation of Tobacco Smokers’ Motivated Processing of Anti-tobacco Commercials. Health Communication, 32(11), 1319–1330.

Connecting with Canadians. (2019). Canadian Centre for Food Integrity. https://www.foodintegrity.ca/research/download-the-2019-research/

Dairy Code strengthens expectations of care for B.C. cows. (2015, July 8). https://archive.news.gov.bc.ca/releases/news_releases_2013-2017/2015AGRI0045-001044.htm

Deckha, M. (2008). Disturbing Images: Peta and the Feminist Ethics of Animal Advocacy. Ethics and the Environment, 13(2), 35–76.

DeGrazia, D. (1999). Animal ethics around the turn of the twenty-first century. Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Ethics, 11, 111–129.

Dillard, J. P., & Shen, L. (2018). Threat Appeals as Multi-Emotion Messages: An Argument Structure Model of Fear and Disgust. Human Communication Research, 44(2), 103–126.

Dumitrascu, V. (2015). Social activism: theories and methods. Rev. Universitara Sociologie. https://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/rvusoclge2015§ion=13

Environment, U. N. (2020, May 15). Preventing the next pandemic - Zoonotic diseases and how to break the chain of transmission. UNEP - UN Environment Programme. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/preventing-future-zoonotic-disease-outbreaks-protecting-environment-animals-and

Faucitano, L., Martelli, G., Nannoni, E., & Widowski, T. (2017). Chapter 21 - Fundamentals of Animal Welfare in Meat Animals and Consumer Attitudes to Animal Welfare. In P. P. Purslow (Ed.), New Aspects of Meat Quality (pp. 537–568). Woodhead Publishing.

Fernández, L. (2020). The Emotional politics of images: moral shock, explicit violence and strategic visual communication in the animal liberation movement. Journal for Critical Animal Studies. 2020; 17 (4): 53-80. https://repositori.upf.edu/handle/10230/47843

Gajalakshmi, C. K., Jha, P., Ranson, K., & Nguyen, S. (2000). Global patterns of smoking and smoking-attributable mortality (Vol. 1139). Tobacco control in developing countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Government of Canada, & Canadian Food Inspection Agency. (2011, December 15). Avian influenza (bird flu). https://inspection.canada.ca/animal-health/terrestrial-animals/diseases/reportable/avian-influenza/eng/1323990856863/1323991018946

Hammond, D., Fong, G. T., McDonald, P. W., Brown, K. S., & Cameron, R. (2004). Graphic Canadian cigarette warning labels and adverse outcomes: evidence from Canadian smokers. American Journal of Public Health, 94(8), 1442–1445.

Historical trends in smoking prevalence. (2017, January 10). Tobacco Use in Canada. https://uwaterloo.ca/tobacco-use-canada/adult-tobacco-use/smoking-canada/historical-trends-smoking-prevalence

Home. (2020, April 6). One Health Initiative. https://onehealthinitiative.com/

Intensive/Factory Farming. (2019, April 4). FAIRR; FAIRR Initiative. https://www.fairr.org/article/intensive-factory-farming/

Kaufmann, B. (2022, June 14). “Baseless”: Province skewers Ottawa over proposed ground meat warning labels. Calgary Herald. https://calgaryherald.com/news/local-news/baseless-province-skewers-ottawa-over-proposed-ground-meat-warning-labels

Key Area Paper--Public Affairs: Smoking and Health - Health Warning Clauses. Bates No. 502605183. (1992). British-American Tobacco Company.

Klara, R. (2012, February 21). Advertising’s Shock Troops. Adweek. https://www.adweek.com/brand-marketing/advertisings-shock-troops-138377/

Koch, J. A., Bolderdijk, J. W., & van Ittersum, K. (2022). Can graphic warning labels reduce the consumption of meat? Appetite, 168, 105690.

Leshner, G., Bolls, P., & Wise, K. (2011). Motivated processing of fear appeal and disgust images in televised anti-tobacco ads. Journal of Media Psychology. https://psycnet.apa.org/journals/jmp/23/2/77/

Livestock systems. (n.d.). Retrieved July 18, 2022, from http://www.fao.org/livestock-systems/en/

Lupton, D. (2012, July 29). What does the yuck factor achieve in anti-obesity campaigns ? The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/what-does-the-yuck-factor-achieve-in-anti-obesity-campaigns-8451

McCarthy, R. (2021, April 14). Cargill temporarily closes Ontario facility due to COVID-19 outbreak. MEAT+POULTRY. https://www.meatpoultry.com/articles/24826-cargill-temporarily-closes-ontario-facility-due-to-covid-19-outbreak

McQuaig, L. (2020, December 16). Keeping the curtains drawn on secretive factory farm industry. The Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/opinion/contributors/2020/12/16/keeping-the-curtains-drawn-on-secretive-factory-farm-industry.html

Mermin-Bunnell, K., & Ahn, W.-K. (2022). It’s Time to be disgusting about COVID-19: Effect of disgust priming on COVID-19 public health compliance among liberals and conservatives. PloS One, 17(5), e0267735.

Morales, A. C., Wu, E. C., & Fitzsimons, G. J. (2012). How Disgust Enhances the Effectiveness of Fear Appeals. JMR, Journal of Marketing Research, 49(3), 383–393.

Moyer, B., MacAllister, J., & Lou Finley Steven Soifer, M. (2001). Doing Democracy: The MAP Model for Organizing Social Movements. New Society Publishers.

Nabi, R. L. (1998). The effect of disgust‐eliciting visuals on attitudes toward animal experimentation. Communication Quarterly, 46(4), 472–484.

Petigara, M., Dridi, C., & Unterschultz, J. (2011). The economic impacts of chronic wasting disease and bovine spongiform encephalopathy in alberta and the rest of Canada. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. Part A, 74(22-24), 1609–1620.

Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act. (n.d.). Retrieved June 23, 2022, from https://www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/96372_01

Reducing tobacco use: a report of the Surgeon General. (2000). US Department of Health and Human Services.

Rozin, P., Haidt, J., & McCauley, C. R. (1999). Disgust: The body and soul emotion. Handbook of Cognition and Emotion, 429, 445.

Saputo. (2015). Animal Welfare Policy. https://saputo.com/-/media/ecosystem/divisions/corporate-services/sites/saputo-com/saputo-com-documents/our-promise/responsible-sourcing/animal-care/2015_saputo-animal-welfare-policy-eng-vfinal.ashx?la=en&revision=e9412ecb-f96e-4263-863d-f3f0a6107dc4#:~:text=High%20quality%20dairy%20products%20begin,any%20act%20of%20animal%20cruelty

Scudder, J. N., & Mills, C. B. (2009). The credibility of shock advocacy: Animal rights attack messages. Public Relations Review, 35(2), 162–164.

Sharp. (n.d.). The politics of nonviolent action, 3 vols. Boston: Porter Sargent. http://omnicenter.org/newsletters/2012/2012-12-31.pdf

Sharp, G. (1968). The politics of nonviolent action : a study in the control of political power. https://www.worldcat.org/title/politics-of-nonviolent-action-a-study-in-the-control-of-political-power/oclc/46341106

Shook, N. J., Thomas, R., & Ford, C. G. (2019). Testing the relation between disgust and general avoidance behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 150, 109457.

Silberman, A. (2022, June 13). Avian flu a threat to New Brunswick poultry industry. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/avian-flu-poultry-new-brunswick-groupe-westco-tom-soucy-1.6484962

Spooner, J. M., Schuppli, C. A., & Fraser, D. (2014). Attitudes of Canadian citizens toward farm animal welfare: A qualitative study. Livestock Science, 163(Supplement C), 150–158.

Sutton, T. C. (2018). The Pandemic Threat of Emerging H5 and H7 Avian Influenza Viruses. Viruses, 10(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/v10090461

Taylor, C. A., Boulos, C., & Almond, D. (2020). Livestock plants and COVID-19 transmission. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1–10.

The Canadian Press. (2022, June 8). More avian flu outbreaks confirmed on B.C., Alberta farms after brief pause in cases. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-food-agency-lifts-restrictions-imposed-after-discovery-of-avian-flu-in/

Tiplady, C. M., Walsh, D.-A. B., & Phillips, C. J. C. (2013). Public Response to Media Coverage of Animal Cruelty. Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Ethics, 26(4), 869–885.

Wiebers, D. O., & Feigin, V. L. (2020). What the COVID-19 crisis is telling humanity. Neuroepidemiology. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7316645/

Yamaji, R., Saad, M. D., Davis, C. T., Swayne, D. E., Wang, D., Wong, F. Y. K., McCauley, J. W., Peiris, J. S. M., Webby, R. J., Fouchier, R. A. M., Kawaoka, Y., & Zhang, W. (2020). Pandemic potential of highly pathogenic avian influenza clade 2.3.4.4 A(H5) viruses. Reviews in Medical Virology, 30(3), e2099.

Zoonoses. (1951). The Lancet, 257(6653), 518–519.